Culture

Culture in Ashihara saw a significant shift from the militarised values imposed by the warlords after the establishment of the centralised government. The glorification of violence came to an end; the renewed regime emphasised the value of the simple beauties of life. Art depicted scenes of nature or humble everyday pleasures, and landmarks were printed on currency instead of prominent militants or imperials.

This softer image of Ashihara changed the traits that were valued by the ordinary citizen: Intellect, shared interest and subtle assertion became the symbols of a good upbringing. Interpersonal conflict came to be seen as a waste of time and a detriment to society.

A self-sufficient lifestyle that provides for loved ones is regarded as the foremost goal of civilians. In the past, Ashiharan culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society. Occupations such as farmers and miners were once considered of a higher status than merchants. This ideal has since become significantly warped; it is no longer the individual farmer or miner that sees any privilege associated with their status over a merchant, but the industry they work for.

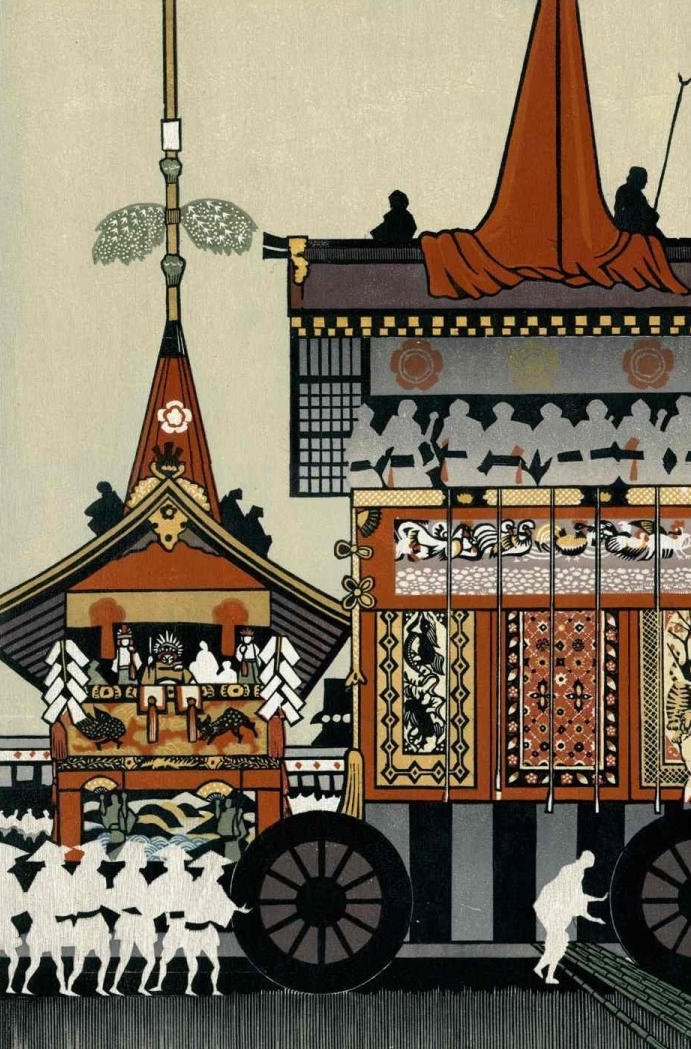

This warp in perspective is present in other cultural keystones; festivals and holidays once considered to be of significant cultural and social import are presently enjoyed as recreational entertainment. While the meaning of these events is often a point of interest, there is little effort spent recalling or honouring their history. One could claim that participation pays a sufficient tribute, but awareness is sparse, particularly among the younger generations.

Common Customs & Manners

Customs in Ashihara are generally defined by virtues and significance that early people learned from the Kami or priest-scholars of the classical ages. Cleansing and preventing impurity, or Kegare, plays an important role in how Ashiharan people conduct themselves in their day-to-day lives.

Shrine visitation, cleaning, and leaving offerings are normal parts of everyday life. Students will go to Kami’s shrine to pray for good exam results, people will pray for good health, to find love, a good harvest, and so on. It is widely understood that Kami will not give somebody what they wish for, but aid their efforts. Kami cannot imbue qualities in somebody that they lack, only embolden their innate resolve. Prayers are mostly meant for support and guidance, which Kami gladly give.

Injury and disease are known to impart Kegare for the danger they pose to life. The same logic applies to pregnancy and birth, which are considered dangerous transitionary periods, as such, it is common sense to not visit shrines during such times.

As a matter of course, cleanliness and restraint are essential aspects of Ashiharan culture that are rooted in everyday interaction. Owning separate footwear for indoors and outdoors, bedrooms, bathrooms, hallways and gardens, not blowing their nose or coughing in public, rinsing themselves with soap before entering the baths and bowing or nodding instead of shaking hands are all common practices. It is also considered inappropriate to eat directly from common dishes provided during meals, people are expected to collect their portions and put them into their bowls or on their plates instead. Most people aren’t keen to dig deep into dishes or share from their plates so as to not inconvenience somebody.

The average citizen feels necessitated to not be a nuisance to others. Teachers and parents alike are often heard quoting the age-old adage ‘respect your seniors’, and stringent forms of politeness and manners are taught even to young school children. Speaking in a loud voice, swearing and acting out are largely associated with the vulgar warrior clans of the past, many of which are poor and considered uncultured.

The invention of streetlights has allowed a bustling nightlife to bloom over the past century. Izakaya are visited more frequently than ever, and drunkards are a common sight when venturing the streets at night. Ordinary civilians often avoid staying out past midnight, due to the prevalence of crime. Theatres and other entertainment venues open their doors until the early hours of the morning when the nightlife and the routine of the working individual intersect.

For a regular civilian in Ashihara, there is precious little they can do against curses besides visiting a shrine. Direct action is largely limited to closing their windows and doors at night, regularly repairing cracks in the walls and replacing and donating old furniture, as well as avoiding stressful situations. Civilians typically purchased Ofuda and Omamori from a shrine, as well as ask a priest or priestess for a warding ritual. Another option that may be available to some civilians is consulting a more enterprising Onmyoji by way of their business cards or consultation office.

Festivals and celebrations are often attributed to a Kami as a form of offering or gratitude for things such as bountiful harvests or the change of the seasons. Significant festivals, such as the ones dedicated to the Kami of the day, Ame-no-asashi-no-hiruma-no-mikoto, and the Kami of all lands, O-kuni-tsukuri, are held throughout all of Ashihara and are organised by imperial shrines.

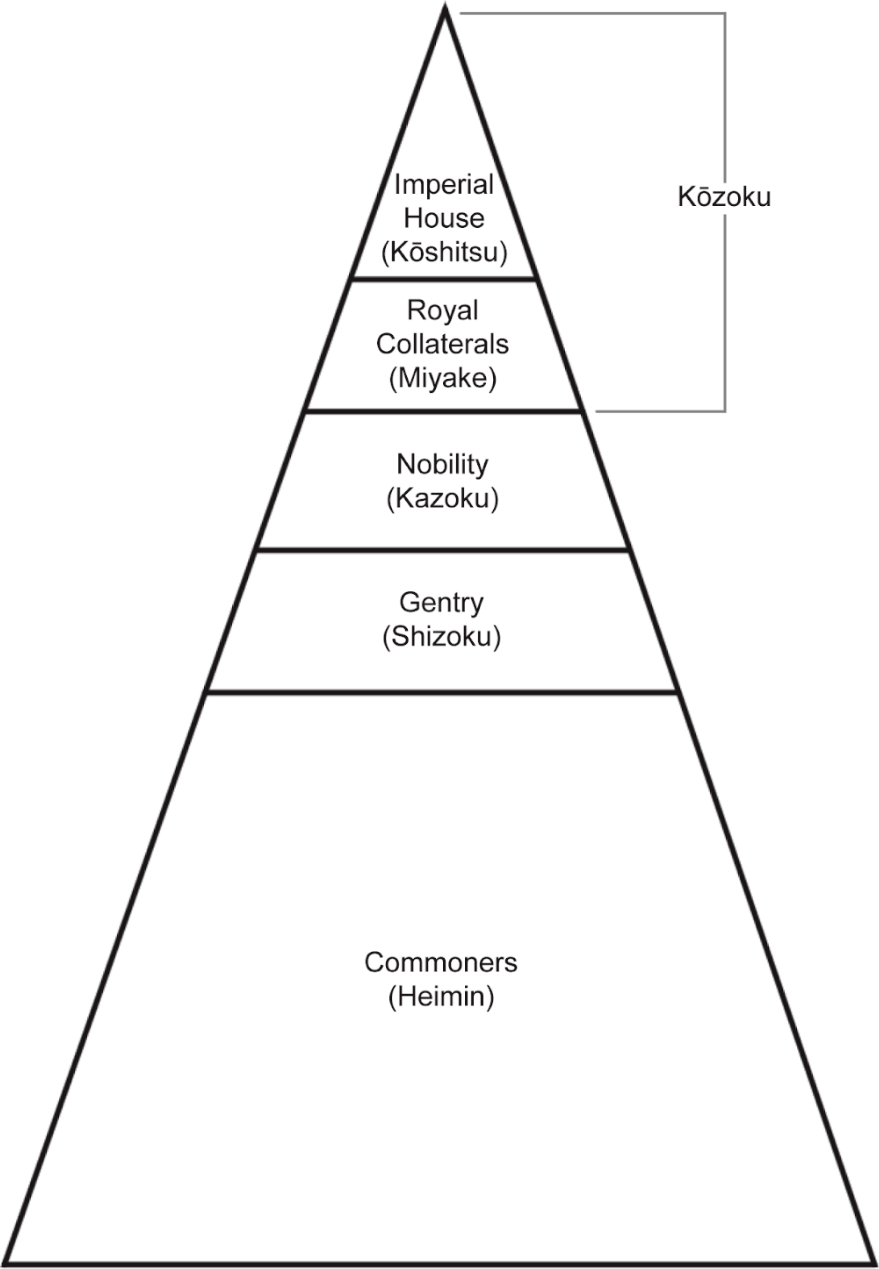

Social Classes

Few denied that modern-day aristocrats hold as much influence as the priest-scholars and philosophers of the past. Ashihara’s aristocracy is without a doubt a political elite, as the basic structure was established in order to restore power to the Emperor after the warrior class had been dissolved.

Subsequently, a modern household’s social status in Ashihara is deeply steeped in the presence, or lack, of aristocratic ancestors. An ordinary citizen is often able to trace their “original” ancestor back to the status of a village headman, samurai, warlord, feudal domain lord, court noble, royal prince, or former emperor. Stories of family downfall (to explain their present commoner status) are heard more often than those of ascension from bottom to top. Ashihara’s elite today nonetheless enjoy ancestral credence allotted to them by their clan’s historical proximity to the Emperor.

When the House of Representatives was established, so was the modern Kazoku system, also referred to as court rank or peerage. The aristocracy saw itself divided into two distinct categories: courtiers, which largely saw functions in the government, and merchants, which grew into the industrial conglomerates known today.

The ex-warrior clans, despite their dedication to the Emperor, were associated with territorial aggression, vulgarity, and a historical penchant for violence. Thus the peerage gave them less weight than clans that supported the imperial household financially or organizationally. The new government often re-authorises these ex-warrior clans with the governorship of their former domains, now known as “prefectures''. This class was known as the Shizoku and possessed no ancestral privileges - effectively demoting the warrior clans to wealthy commoners.

The positions available to someone of the aristocracy will depend on their placement in the Kazoku system. The Kazoku system places houses of import into five distinct ranks, in order of proximity to the Imperial Household and their accumulated wealth: Ōshaku (王爵, Son of Imperial/Duke), Kōshaku (侯爵, Marquess), Hakushaku (伯爵, Count), Shishaku (子爵, Viscount), and Danshaku (男爵, Baron).

Discrimination

To be considered of “noble origin”, a member of Ashihara’s elite must abide by rigid court manners. The aristocrats distinguish themselves from the ordinary civilians through “the civilising process”, which transforms natural bodily functions such as sneezing, coughing or spitting into acts of vulgarity. The aristocracy is embodied by this strict segregation between the natural body and the political body which represents a symbol of the wealth and prestige of their clan.

Those who fail to abide by these rigid rules will often see themselves, and by extension, their family members, indirectly dismissed and isolated from their ‘peers’. Understanding these rules and micro-interactions is an important social skill to stay relevant among the elite. An individual who hails from a family of the Danshaku rank will need a contact that is trusted by an informant of a designated Koshaku family to even have a shot of speaking with a representative.

Ironically, for those among the elite, a commoner is less disruptive than those of lower Kazoku rank. Unlike the former, which amounts to more or less an identical homogeny of ‘poor people’, the latter group endlessly toils to be acknowledged by those superior in rank in hopes of climbing the ladder - the aristocratic court is full of competitors, copycats, schmoozers and eyesores.

Instead of the elite having a low opinion of the commonwealth, it is that they can spend most of their lives not forming one at all. A lifestyle that has come under scrutiny in recent times.

Clans

The divide of Ashihara’s social groups is deeply rooted in ancestral lineage, and nearly every citizen can trace back their lineage to a particular clan. Regular citizens who are part of the Heimin are normally from families whose clans have either been dissolved, or removed from a clan’s line of succession. Even the lack of an existing clan in one’s ancestry speaks volumes about their social status; the poorest farmers still served a daimyo, after all.

The most powerful clans were discouraged from usurping the imperial family. In exchange for their disqualification from the imperial throne, they were given land and a position in the imperial court. Historically, a clan’s influence was determined by the amount of territory they owned.

The sway these clans held on Ashihara’s politics, ironically, has seen little change throughout history. In spite of this, the current government claims that the clan system has officially been dissolved.

Clan Structure

It must be noted that a clan can consist of many families and households with their own internal politics. Realistically, a clan can have many different families under its banner, all of which share the same name. Clans that have outgrown themselves may have their numerous branches named by the emperor as a means of differentiation.

Authority in a family is built on the Honke-Bunke system.

Honke

The Honke is the administrative household which holds authority over the family’s territory. They manage the family’s affairs and resources, and delegate tasks to lower branches of the family such as the myriad Bunke. Because of this authority, the Honke historically serves as the face of the family and partakes in political negotiations with other branches.

In modern day, members of a Honke often have positions in the government, or otherwise elite professions such as lawyers, doctors, or moguls.

Bunke

Bunke are branch households that are subordinate to the Honke. Bunke can have several designations, such as taking care of ceremonies, overseeing the treasuries, or providing resources for the Honke. In ordinary cases, Bunke are entrusted to direct relatives of the Honke. Exceptions can be made for trusted individuals or bereaved spouses.

The influence of a Bunke over the family is determined by their familial proximity to the Honke. When the head of the Honke passes away or abdicates with no chosen successor, the nearest family member is obligated to take their place. Authority is then transferred to their Bunke, making them the new Honke.

Jinke, Shikike and Bekke

While the Honke-Bunke relationship is central to the clan’s overall structure, certain branches of the family may be given corollary tasks. These branches are given names that distinguish them from the Bunke, namely Jinke, Shikike, and Bekke.

A Jinke is a Bunke put in charge of a family’s Kami worship and school of Onmyodo.

A Shikike is a ceremonial Bunke that is in charge of overseeing rites and traditions within a Honke, such as a coming-of-age ceremony or taking care of ancestral burial sites and shrines.

Historically, clans could grow so large that they needed to employ the clanless, or citizens outside their clan, to help maintain it. These branches were called Bekke and were exempt from the line of succession for a family, unlike Bunke.

Succession

For a child to be an eligible heir to their family’s household or business, they must be the eldest child of their parents. A sibling can only be appointed a successor when the heir has passed away or resigned (due to illness, age, etc). Siblings are not raised with the expectation that they may inherit the main household. The heir may entrust important functions within the family to their siblings, or a cousin if they have no siblings, though.

The heir inherits the household, takes care of their ageing parents and picks up the family’s affairs. They are not permitted to marry the heads of different households without merging their families. The siblings of the heir will often marry into other families or begin branch households of their own.

Family Culture

Stemming from Ashiharan values that emphasise a peaceful household and respectful children, an ideal marriage is stable and built upon mutual understanding of a partners’ wishes for the future they will build together. This is in part because newlyweds will be upholding a business or becoming part of a larger clan. Though love marriages have sprouted up in these times of professional wages and financial independence, they are rare and not particularly welcomed, as a lack of familial support reflects poorly upon the couple, and indicates impracticality.

In that vein, relationships function similarly. Though arrangements for aristocracy can be decided as early as infancy, the average youth will often become engaged to individuals in their community they are already well-acquainted with. Arrangements where partners have never met are rare, as among the aristocracy most couples will meet during a formal introduction. The practice is left over from the age when the sole purpose of marriage was to form allegiances between clans. Venerating the authority of the head of the household has become less frequent, but traditional families still expect to receive marital gifts such as money or land.

Individuals are expected to do their utmost to contribute to their family and take precedence to their eldest’ wishes until the day they too become family elders. Common expectations are being financially trustworthy, having a healthy moderation for drinking and other vices, as well as the ability to provide sufficient heirs and raise them to adulthood. And, in the case of aristocracy, arrange betrothals beneficial to their family. To forego these responsibilities is to effectively denounce oneself from the family's intricacies: exceptions are only made for individuals in high-risk professions or cases such as the Isshin Renritsu Kubun.

While clans largely revolve around the decisions of the house leader, leadership in a family unit is much more spread out. Spouses with offspring are considered their own family unit and are expected to set a good example for their children. They are meant to set a good example in manners and intellect and pass on familial teachings in day-to-day life so that their grandchildren will be raised the same way. Exemplary children are patient, quick to stand up to challenges, and are encouraged to speak articulately; after all, they will soon grow up to represent their families in society.

Pregnancy, Birth, & Childhood

The birth of a child is an important milestone in Ashihara. One month after the baby is born, they are brought to a shrine to thank the Kami in a rite known as Miyamairi. A grandparent or relative of the mother carries the child, as the mother herself is considered kegare from childbirth and cannot visit a shrine. The infant is dressed in fine robes bearing the crest of their family if the family still has one, and is placed under the protection of a Kami of the family’s choosing.

Childbirth itself is rife with uncertainty, and a serious risk of death to both parent and child. As precaution, most households have a separate room, or ‘birth chamber’, for housing pregnant family members. Wealthy families may have a whole wing or an entire separate estate for the sole purpose of housing a pregnant family member. The expecting parent and their entourage of midwives will stay within the birth chamber until the child is born and confirmed healthy.

A Priest may be present to purify the birth chamber and anybody that assisted with the birth afterwards. In certain cases, Onmyoji may be invited on the off chance that something is amiss.

Infants are typically not given their ‘childhood name’ until twelve days have passed. These names are given to the child not by the parents, but by their relatives. In more affluent families, this name may be bestowed to them by a Priest or a scribe.

Coming of Age Ceremonies

Participation in adult society is marked by a Coming of Age Ceremony between a child’s 13th and 15th birthday. During the ceremony, the child will be ritually enrobed into hitoe for girls and kariginu for boys, and an adult hairstyle, upon which they are celebrated by their household. A portrait is made of the celebrant to memorialise the event.

The event concludes after the celebrant is given their adult name going forwards, chosen by either their parents, a scribe or a priest to commemorate the path they shall walk. From this moment, the celebrant is able to participate in society - they can begin working and climb in social rank, participate in courtship, and have a bethrotal arranged, though marriage is usually reserved until a later time for dowry.

Mortuary Rites

Funerals are quick affairs and officiated by multiple Priests, with much of the planning managed by the deceased’s eldest surviving relative. Onmyoji are invited to watch over the rites in the event of unexpected occurrences.

Immediately after the death of a loved one, the family ancestral altar is covered to keep the deceased’s spirit from entering it. The deceased’s body is then washed and allowed to rest, food offerings are made, and a sacred sword or sacred mirror is laid by the deceased’s body. Their passing is then announced to the Kami which reside in the family's ancestral shrine.

The Priests hold a purification ceremony to cleanse the eventual gravesite, themselves, and the deceased’s mitama. Only then can a wake be held for mourners to give their condolences, and is only held the day before the funeral.

Mourners must partake in cleansing themselves before entering the wake much in the same way they would before entering a shrine: by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths with clean water. When the wake is done, the Priest transfers the mitama to a reiji, a wooden tablet. The reiji is kept in a separate room and is protected by an Onmyoji until the coffin leaves the house.

The coffin is brought to a crematorium, and only the deceased’s closest relatives and friends may be present. A Priest will offer a prayer, and the body is set ablaze. The bones are picked up with a pair of chopsticks by the head mourner, and placed in a vase alongside the ashes. This vase is brought home and is kept there as kegare leaves the deceased’s ashes. A temporary altar is also set up in the home, upon which the reiji is kept and offerings are made for fifty days.

During this time the family cannot visit any shrines, at risk of bringing this kegare with them. The ashes are typically cleansed of kegare after fifty days, but some families may opt to keep the vase in their households for longer. Once cleansed, these ashes are entombed at the purified gravesite. The reiji is also moved from the temporary altar and placed within the ancestral altar. A purification ceremony is also held to remove the kegare brought on by death in the household.

It should also be noted that all people who had some participation in the funeral process, whether it be simply giving condolence money or even assisting in the wake, must purify themselves with cleansing salt. This is to ward off kegare brought on by the deceased’s passing.

Workplace Culture

Influence over a community has fallen largely into the hands of the wealthy and resourceful, which led to the organised structure of family businesses seen today. The simple, humble lifestyle that was once considered to be the cornerstone of Ashihara’s society was replaced with a lifestyle that is constantly on-the-clock; time has become a commodity, and Ashiharans now tend to maintain a more structured lifestyle.

The ideal worker:

- Wakes up early, typically before sunrise

- Eats breakfast with their family

- Goes to work for approximately 8 hours or more

- Buys groceries if needed

- Returns home

- Prepares and eats dinner

- Goes to the bathhouse, sometimes with family

- Goes to sleep

Familial and religious traditions function around these rigorous schedules. The Kami are worshipped less as a necessity, and more as a perk when one finds the time. Prayer and worship have to bend in accordance with the lifestyle of the average worker, a prominent instance were radio stations broadcasting shrine-mandated prayer channels during commute hours.

The Ashiharan Calendar

One year is 12 months with 372 days. Each month has 31 days, and each month is approximately 2 and a half weeks, with each week having 12 days.

Dates may be denoted as DD/MM or Month Name, Day. For example, someone who is born on the first day of the second month would have their birthdate denoted as 1/2 or Shunbun 2.

Isshin Renritsu Kubun currently takes place in the year 1887.

| Months |

|---|

| Risshun (Beginning of Spring) |

| Shunbun (Spring Equinox) |

| Kokuu (Grain Rains) |

| Rikka (Beginning of Summer) |

| Geshi (Summer Soltice) |

| Shousho (Lesser Heat) |

| Risshu (Beginning of Autumn) |

| Shuubun (Autumn Equinox) |

| Kanro (Cold Dew) |

| Ritto (Beginning of Winter) |

| Touji (Winter Solstice) |

| Daikan (Greater Cold) |

| Days of the Week |

|---|

| Ichiyoubi |

| Niiyoubi |

| Sanyoubi |

| Yotsuyoubi |

| Goyoubi |

| Rokuyoubi |

| Shichiyoubi |

| Hachiyoubi |

| Kuyoubi |

| Jyuuyoubi |

| Yasuyoubi |

| Sameyoubi |