The imperial court celebrates the coronation of the Her Radiance the Emperor, the central transport company completed the cross-region railway network after several painstaking decades, and the simmering tensions between the eponymous San-meike and Industrialists are threatening to boil over.

And amongst those are smaller tales yet to become: The recent establishment of the Isshin Jouyaku, an act passed in an attempt to smoothen the aforementioned tensions between old and new blood. With it, the beginning of a permanent shift in society begins to stir in the Capital.

In the wake of the challenging age to come, the Isshin Renritsu Kubun was formed to guide and protect Ashihara’s citizens through a future yet uncharted.

The emergence of an Industrial age

The reign of the former empire came to a bleak end with the Asatera clan’s crushing victory in the war. Ashihara was unified under the banner of the current imperial household, House Hinonishi. The Emperor dispersed the warrior class, and the fledgling government established by the imperial household, the Nakatsukasasho, centralised the flow of resources; freedom for art, education, philosophy and innovation were given space to re-emerge. Currency was no longer controlled by warring clans, and Ashihara gained a welcome age of “normalcy” after the 300-year-war.

An opportunity arised for the San-meike, a triad of clans that remained neutral during the war. They formed the Onmyoryo, which led to the opening of a portion of their archives for public use. Documented records and education were now more accessible than ever before: a cultural reform took hold of the commercial capital. The noble class’ grip on the commoners rapidly begun to slip. Many civilians learned how to read and write, and with it, learn.

Medicine and hygiene improved over the years, and the average household in Ashihara suddenly had more mouths to feed. Resources like food, fuel, and fabrics staggeringly rose in demand. With education came the capability to understand, and for many labourers at the time, to criticise. Options were sparse for those in charge; hear the masses, or regret it for generations to come. Crucial sectors necessary to Ashihara’s economy were streamlined after much trial and effort over the decades, most importantly the agricultural, manufacturing and mining sectors.

Control fell back into the hands of the labourer and the citizen. artisan unions and conglomerates of various categories sprang up all across Ashihara. These "industries," as they were called, and their directors lost interest in the largely obsolete regulations of not only the imperials, but the fear-mongering San-meike.

The spiritual decline of Ashihara

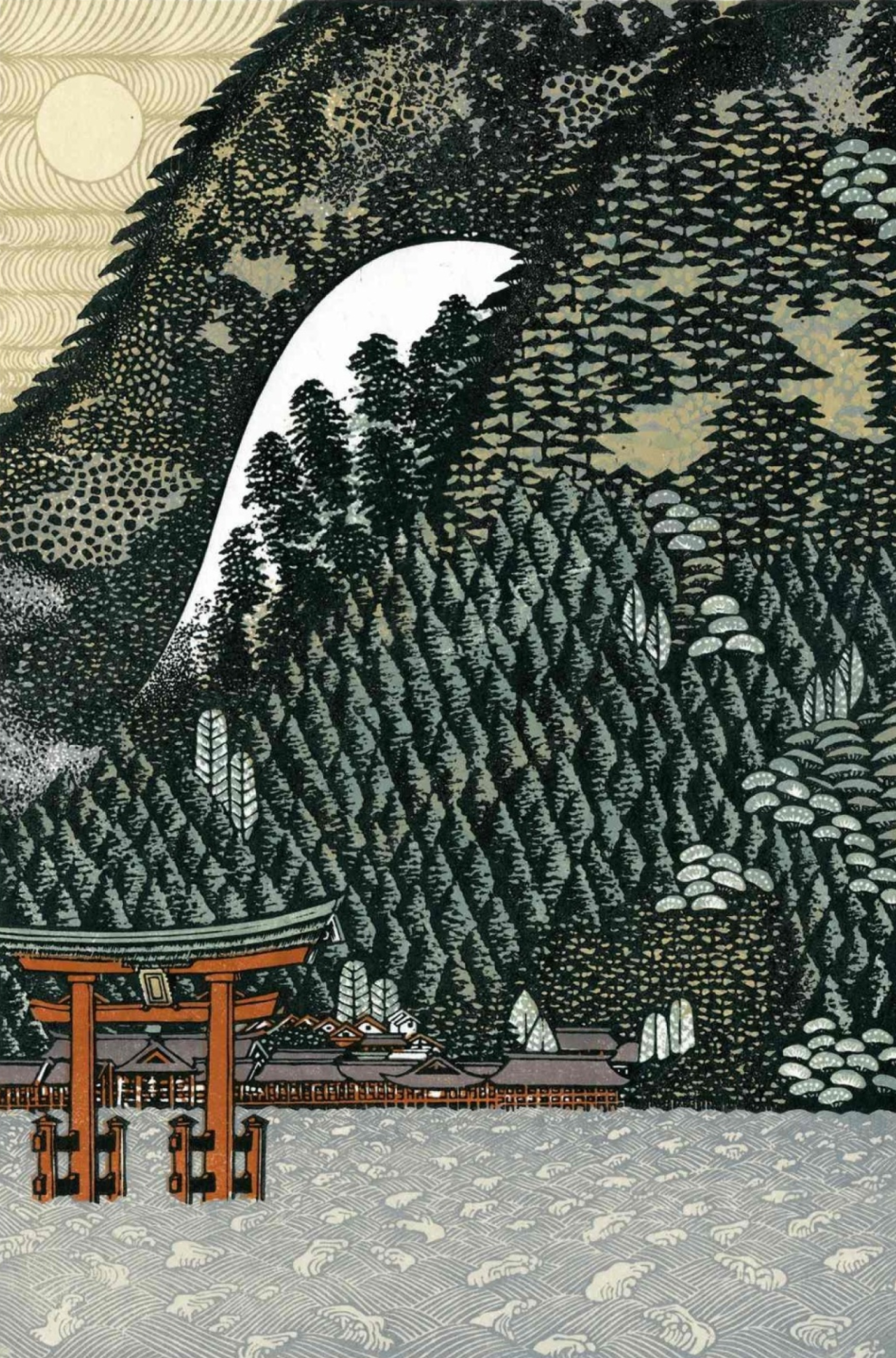

People in Ashihara grow up knowing that the Kami, O-kuni-tsukuri, rules the domain of Ji, the earth. The Kami of Ashihara share this realm with humans as their home; a presence not only documented, but lived. Humans pay their respects by visiting shrines, they leave offerings and pray for better days, as they have since Ashihara’s earliest days.

But it’s rare to find a dedicated priest or priestess who was not born and raised as one. And there are few who would proudly call themselves an Onmyoji today. Citizens still hold priests in high regard, mostly because a priest doesn’t dread what he doesn’t know, instead of genuine respect for what he knows.

Worship is little but a mindful activity to the majority of Ashihara’s corporate busybodies, who have forgotten it’s necessity. The modern worker doesn’t distinguish between illness and curses. Rice won’t hull itself, and the Kami won’t pay their taxes. The San-meike are similarly obsolete to them, as are their teachings of the Go-dai. Like the days of inexplicable catastrophes or Onmyoji moving mountains, the general public believes they belong in history books.

Unrest in Ashihara

People in Ashihara grow up knowing that the Kami, O-kuni-tsukuri, rules the domain of Ji, the earth. The Kami of Ashihara share this realm with humans as their home; a presence not only documented, but lived. Humans pay their respects by visiting shrines, they leave offerings and pray for better days, as they have since Ashihara’s earliest days.

But it’s rare to find a dedicated priest or priestess who was not born and raised as one. And there are few who would proudly call themselves an Onmyoji today. Citizens still hold priests in high regard, mostly because a priest doesn’t dread what he doesn’t know, instead of genuine respect for what he knows.

Worship is little but a mindful activity to the majority of Ashihara’s corporate busybodies, who have forgotten it’s necessity. The modern worker doesn’t distinguish between illness and curses. Rice won’t hull itself, and the Kami won’t pay their taxes. The San-meike are similarly obsolete to them, as are their teachings of the Go-dai. Like the days of inexplicable catastrophes or Onmyoji moving mountains, the general public believes they belong in history books.

As a fledgling subdivision established under the Onmyoryo, the Isshin Renritsu Kubun (abbreviated to the IRK) strives to neutralise harmful and auspicious forces, known as ayakashi or yokai, which continue to disrupt Ashihara’s society in spite of declining belief.

Members of IRK, the Reritsuin, are able-bodied individuals who have previous experience as Onmyoji. Renritsuin must dedicate their lives to the pursuit of peace, harmony, and public safety.

IRK requires little else other than one’s ability to work in teams and prior experience with the basic fundamentals of Onmyodo, such as a mastery of the Go-dai, identifying and expelling curses. The San-meike expects Renritsuin to observe their methods alone: Different branches of Onmyodo are strictly prohibited, and any spell or Shikigami a Renritsuin creates must first be approved by the Onmyoryo.

The Onmyoryo, or Ministry of Divination

The Isshin Renritsu Kubun receives most of its resources, funding and projects from the Onmyoryo. In most cases, the Onmyoryo is given orders by the Ministry of Civil Affairs when an incident cannot be solved by the relevant public departments. Concerns such as inexplicable bankruptcy, wet books whose pages never dry, and noise with no discernable source are all simple verdicts that may be picked up and forwarded to the IRK.

The Onmyoryo supplies IRK with the necessary resources to perform their duties as Onmyoji; such as specialised paper, dragon-blood ink, incense, warding rope, purification needles, and access to the Onmyoryo’s arsenal of registered weaponry. The San-meike's archives and expertise are open for Renritsuin to make use of as much as they need.

Renritsuin

The main tasks of a Renritsuin sound simple in theory: correctly identify the influence of auspicious or harmful forces in a situation, and expel or appease them as needed.

But their job is complicated by a multitude of factors; dismissal by cynics, time and financial constraints, pressure from industries and the press, and the average citizen’s refusal to risk their reputation. Renritsuin will spend most of their time delving into the central library or interviewing the locals, gathering as many clues as they can to disclose what they are dealing with in the first place.

The IRK operates within a legal twilight, with its authority questioned but rarely contested purely due to its expertise in its field. A rally the IRK uses is the historical idiom “Resilience and Remembrance” originated from the San-meike. Renritsuin embody this with an unwavering devotion to the people and the Kami of Ashihara.

Most Renritsuin will find that a large portion of their assignments boils down to putting superstitious elderly or scared children at ease. A simple matter of updating and filing the case into the Onmyoryo’s archives, and moving on to the next assignment. While certainly not as exciting or dangerous as sealing and expelling harmful spirits, it is these mundane tasks that are exactly what prevent yokai from taking root in communities.